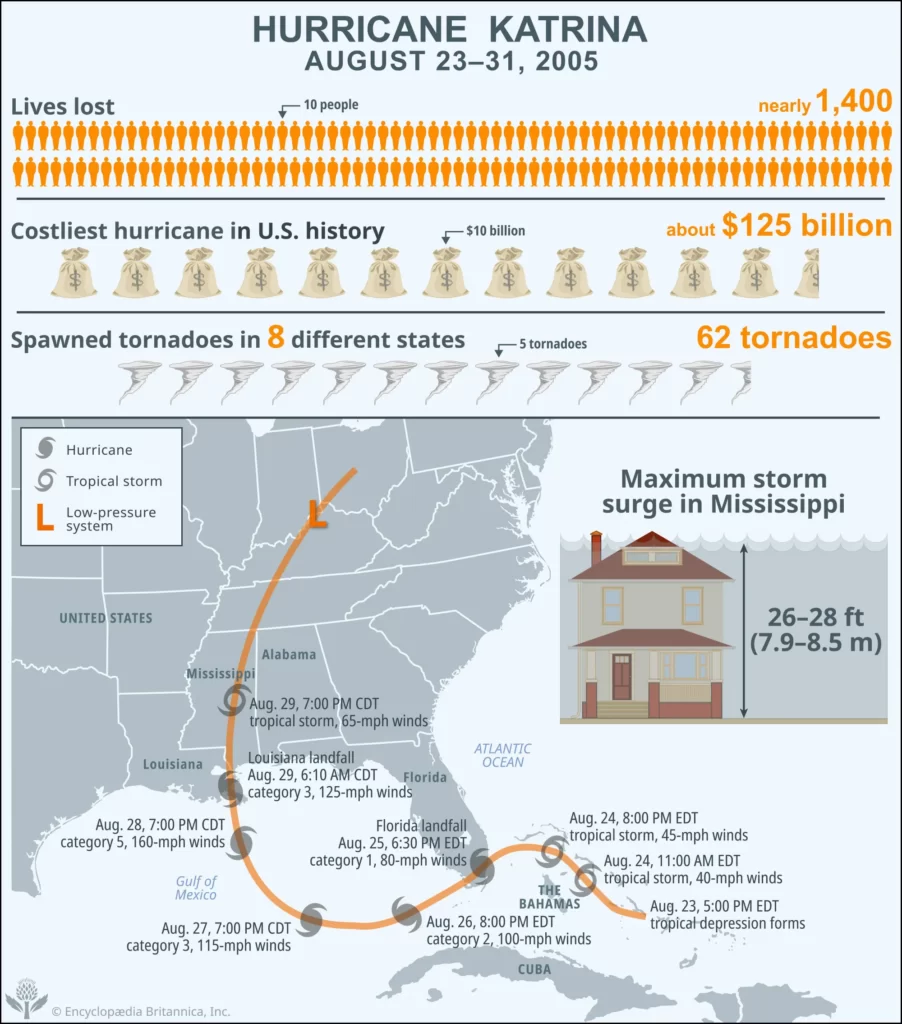

On 29 August 2005, Hurricane Katrina made its second and third landfalls as a Category 3 hurricane, unleashing one of the deadliest and costliest natural disasters in United States history. Hurricane Katrina, catastrophic tropical cyclone and its aftermath claimed nearly 1,400 lives. Some two decades after the hurricane, the lingering effects of Katrina continue to influence the economy and culture of the Gulf Coast.

Early development and landfall in Florida

The weather system that would later become Hurricane Katrina emerged on August 23, 2005, as a tropical depression over the Bahamas, approximately 350 miles (563.3 km) east of Miami. Over the next two days it gathered strength, growing into a tropical storm by 11:00 am local time on August 24, and centered over the Bahamas. Throughout the evening of August 24 and the morning of August 25, it moved west and ultimately turned on a path toward southeastern Florida, reaching the Straits of Florida by 3:00 pm. Two hours later, as Katrina neared the northern suburbs of Miami, weather officials from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) National Hurricane Center (NHC) announced that it had intensified into a weak category 1 hurricane with maximum sustained winds of 75 miles (120.7 km) per hour.

Katrina made its first landfall at about 6:30 pm on August 25 between Miami and Hollywood, Florida, as a category 1 hurricane with sustained winds of up to 80 miles (128.7 km) per hour. As wind and rain continued to lash the Florida peninsula over the next six hours, many areas along Katrina’s path received more than 5 inches (12.7 cm) of rain.

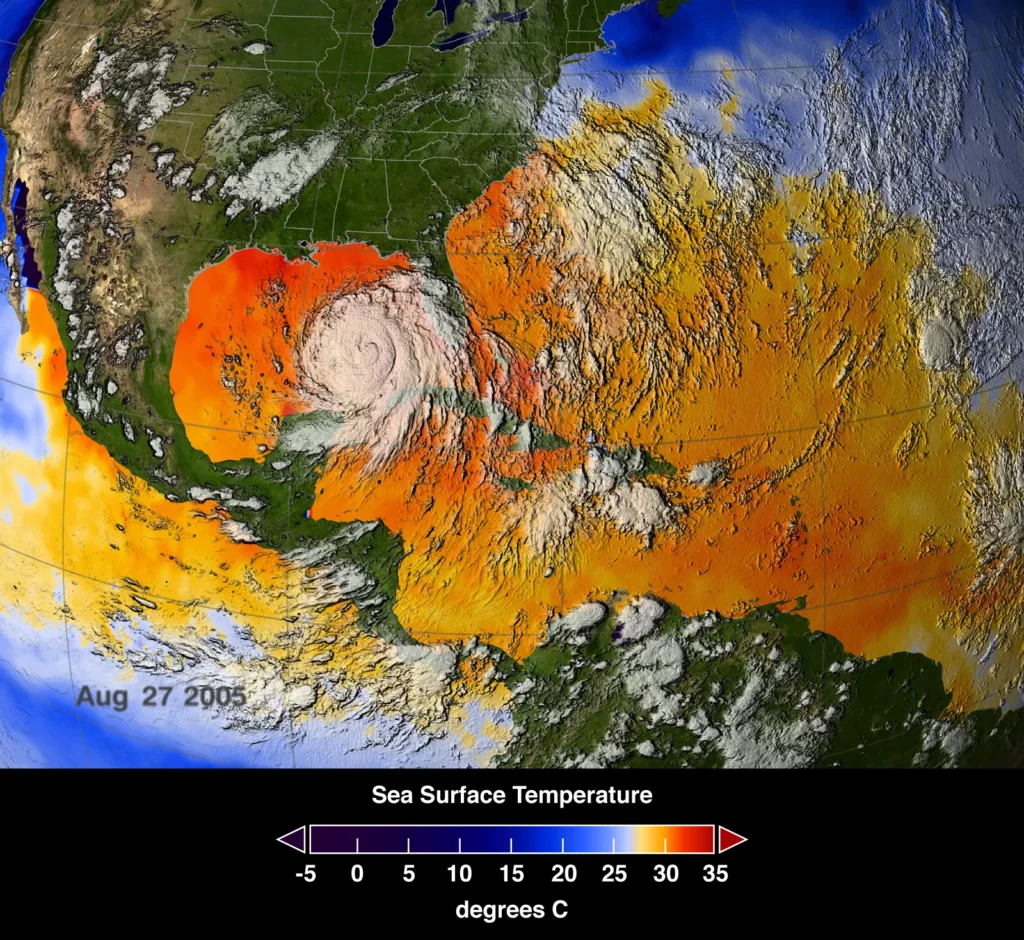

Katrina weakened to a tropical storm over the peninsula, but as the storm traveled west and passed into the warm waters of the Gulf of Mexico overnight, it quickly grew in strength, becoming a category 2 hurricane by 8:00 pm on August 26. At 5:00 am on August 27, Katrina approached the center of the Gulf of Mexico, and NHC weather officials announced that it had intensified into a category 3 storm with sustained 115-mile- (185-km-) per-hour winds. Satellite images taken at this time revealed that Katrina’s circulation had virtually covered the Gulf of Mexico.

By the morning of August 28, Katrina had grown into a massive category 5 storm with winds in excess of 160 miles (257.5 km) per hour; NHC bulletins noted that the storm had turned northward, threatening the coasts of Louisiana, Alabama, and western Florida. Only a few hours later, Katrina had become one of the most powerful Atlantic storms on record, with winds topping 170 miles (273.6 km) per hour.

Landfall along the Gulf Coast

At 6:10 am on August 29, Katrina made landfall at Buras in Plaquemines Parish, Louisiana, approximately 50 miles (80.5 km) southeast of New Orleans. Most officials noted that the storm came ashore as a strong category 3 hurricane, with maximum sustained winds of 125 miles (201.2 km) per hour. It continued on a course to the northeast, crossing the Mississippi Sound and making a second landfall later that morning near the mouth of the Pearl River.

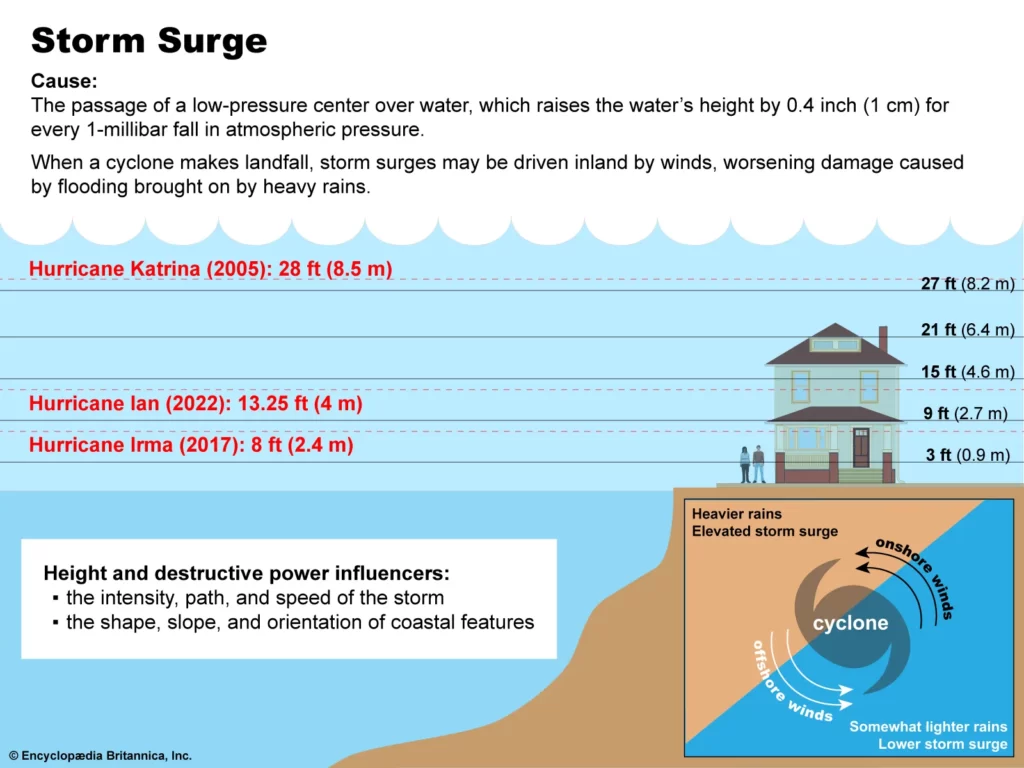

In Mississippi a storm surge more than 26 feet (7.9 meters) high slammed into the coastal cities of Gulfport and Biloxi, devastating homes and resorts along the beachfront. Along some parts of the Mississippi coast, the storm surge was reported to have been as high as 28 feet (8.5 meters) above normal tide levels.

Damage

In New Orleans, where much of the greater metropolitan area is below sea level, federal officials initially believed that the city had “dodged the bullet.” While New Orleans had been spared a direct hit by the intense winds of the storm, the true threat was soon apparent. The levee system that held back the waters of Lake Pontchartrain and Lake Borgne had been completely overwhelmed by 10 inches (25 cm) of rain and Katrina’s storm surge. Some levees buttressing the Industrial Canal, the 17th Street Canal, and other areas were overtopped by the storm surge, and others were breached after these structures failed outright from the buildup of water pressure behind them. The area east of the Industrial Canal was the first part of the city to flood; by the afternoon of August 29, some 20 percent of the city was underwater.

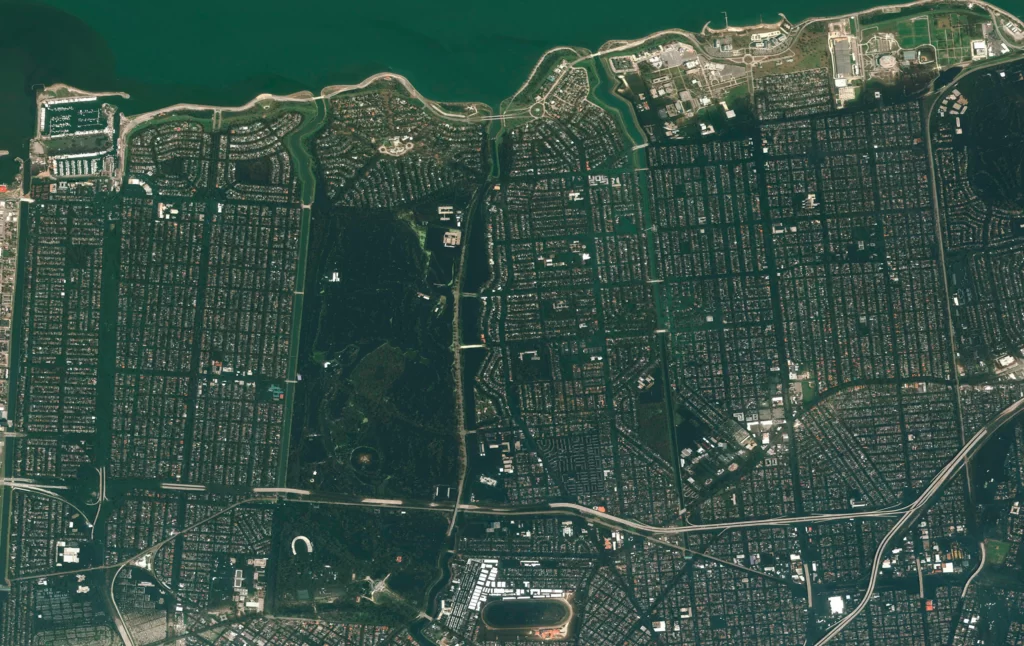

Before and after Hurricane Katrina

These satellite images compare New Orleans before (March 9, 2005) and after (August 31, 2005) Hurricane Katrina, highlighting widespread flooding and devastation from levee failures and overwhelmed infrastructure. Using your mouse or arrow keys, move the slider from side to side.

New Orleans Mayor Ray Nagin had ordered a mandatory evacuation of the city the previous day, and an estimated 1.2 million people left ahead of the storm. However, tens of thousands of residents could not or would not leave. They either remained in their homes or sought shelter at locations such as the New Orleans Convention Center or the Louisiana Superdome. As the already strained levee system continued to give way, the remaining residents of New Orleans were faced with a city that by August 30 was 80 percent underwater. Many local agencies found themselves unable to respond to the increasingly desperate situation, as their own headquarters and control centers were under 20 feet (6.1 meters) of water. With no relief in sight and in the absence of any organized effort to restore order, some neighborhoods experienced substantial amounts of looting, and helicopters were used to rescue many people from rooftops in the flooded Ninth Ward.

Aftermath

On August 31 the first wave of evacuees arrived at the Red Cross shelter at the Houston Astrodome, some 350 miles (563.3 km) away from New Orleans, but tens of thousands remained in the city. By September 1 an estimated 30,000 people were seeking shelter under the damaged roof of the Superdome, and an additional 25,000 had gathered at the convention center. Shortages of food and potable water quickly became an issue, and daily temperatures reached 90 °F (32 °C). An absence of basic sanitation combined with the omnipresent bacteria-rich floodwaters to create a public health emergency.

It was not until September 2 that an effective military presence was established in the city and National Guard troops mobilized to distribute food and water. The evacuation of hurricane victims continued, and crews began to rebuild the breached levees. On September 6, local police estimated that there were fewer than 10,000 residents left in New Orleans. As the recovery began, dozens of countries contributed funds and supplies, and Canada and Mexico deployed troops to the Gulf Coast to assist with the cleanup and rebuilding. The US Army Corps of Engineers pumped the last of the floodwaters out of the city on October 11, 2005, some 43 days after Katrina made landfall. Ultimately, the storm caused more than $125 billion in damage (equal to more than $200 billion in 2024 dollars), and the population of New Orleans fell by 29 percent between the fall of 2005 and 2011. Although many residents returned and the city’s population increased to about 400,000 by 2020, it still remained some 20 percent below its population in 2000.

A decade after the storm, the US Army Corps of Engineers acknowledged flaws in the construction of the city’s levee and flood-protection system. In some parts of the city, levees and sea walls were not tall enough to hold back the water; in others floodgates did not close properly, and some structures collapsed entirely. Complicating matters was the fact that many parts of the New Orleans area vulnerable to flooding were not formally listed as flood zones by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), so homeowners were not advised of their predicament, and they did not have flood insurance; both factors contributed to higher overall damage totals. Since then, New Orleans’s flood-protection system was bolstered by $15 billion in federal funds, which were used to increase the heights of earthen berms and upgrade floodwalls and floodgates. These defenses held after Hurricane Ida, a category 4 storm, made landfall close to the city in August 2021.

Also read: Tsunami alerts for US, Japan, Philippines after massive Russia earthquake

For more videos and updates, check out our YouTube channel.

Source: Britannica.com