More than three decades after the brutal killing of his parents shocked Beverly Hills and captivated America, Erik Menendez has been denied parole in California. The decision comes amid a renewed wave of public interest in the case — fuelled by Netflix dramas, TikTok debates, and the enduring fascination with 1990s true crime stories.

The brothers shot the pair more than a dozen times in 1989, Erik even reloading the gun and continuing to fire on his mother. He and his brother have long claimed self-defence and said they were being abused sexually.

During their trials, the brothers claimed the killings were done in self-defence and that they had suffered years of emotional and sexual abuse at the hands of their parents.

Prosecutors, though, argued they were greedy, entitled monsters who meticulously planned the killings then lied to authorities investigating the case while going on a $700,000 (£526,000) spending spree using money they had inherited.

The pair were not arrested until police got word of their admissions to a psychologist.

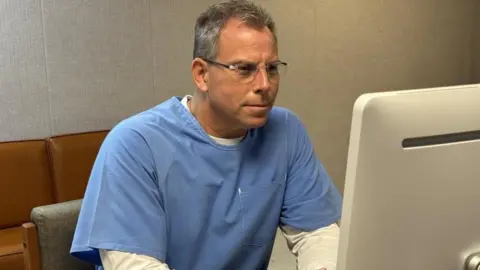

Erik’s parole hearing

Erik, 53, appeared yesterday, virtually from the San Diego prison where he is serving a life sentence, his first parole hearing since being re-sentenced earlier this year. The California parole board ruled that he continued to pose a public safety risk, citing prison violations and the “brutal nature” of the 1989 murders. He will be eligible to reapply in three years.

Board commissioner Robert Barton, who listened to testimony for more than 10 hours with a panel before denying Erik’s parole, said he believed Erik was not yet ready for release.

“I believe in redemption, or I wouldn’t be doing this job,” he told Erik at the end of the marathon hearing. “But based on the legal standards, we find that you continue to pose an unreasonable risk to public safety.”

The board took issue, specifically, with his violations in prison and past criminal activity before killing his parents.

“Contrary to your supporters’ beliefs, you have not been a model prisoner and frankly, we find that a little disturbing,” Barton said, bluntly telling him he now had “two options” for his future.

“One is to have a pity party,” Barton told Erik. “Or you can take to heart what we discussed.”

During Thursday’s hearing, a prosecutor from the Los Angeles district attorney’s office argued against Erik’s release, saying positive changes in his behaviour were only motivated by a chance at release. They argued he was “still an unreasonable risk to society” and that “he has no insight into his crimes”

During the nearly-full-day hearing, the panel asked him about the killings, his relationship with his parents and his attempts to cover up guilt in the murders. He grew emotional at times, describing the moments he opened fire on his parents, Jose and Kitty Menendez, with a shotgun as they watched TV in their Beverly Hills mansion.

“I just want my family to understand that I am so unimaginably sorry for what I have put them through from Aug. 20, 1989 until this day, and this hearing,” Erik said during the hearing, before he knew his fate.

“If I ever get the chance at freedom, I want the healing to be about them,” he said. “Don’t think it’s the healing of me – it’s the healing of the family. This is a family tragedy.”

Lyle’s parole board panel

His brother Lyle Menendez, 56, is set to face a separate parole panel. Both were convicted of gunning down their parents, José and Kitty Menendez, in their Beverly Hills mansion in what prosecutors described as a “cold-blooded” and financially motivated killing. The brothers, however, have long argued that they acted in self-defence after years of sexual and emotional abuse.

Lyle is set to appear before a different parole board panel on Friday morning. The brothers’ conduct behind bars and before the 1989 killings is viewed differently, meaning that Lyle’s case could prompt a different decision from the parole board.

During Thursday’s hearing for Erik, a coalition of relatives, who have long advocated for the brothers’ release, testified on Erik’s behalf – saying he had changed.

Hi aunt Teresita Menendez-Baralt broke down in tears as she spoke before the panel, telling them she had forgiven Erik for killing her brother and the years of trauma he caused their family.

She said that she was dying from stage four cancer. “The truth is I do not know how much time I have left. If Erik is granted parole, it would be a blessing,” she told them.

“I hope I live long enough to welcome him into my home, to sit at the same table, to wrap my arms around him – that would bring me immeasurable peace and joy.”

From 90s courtroom drama to streaming obsession

The Menendez trial, televised in the early 1990s, became one of America’s first modern “media trials.” It was a staple of tabloid headlines, daytime news programmes, and talk shows — a spectacle that blurred the lines between tragedy and entertainment.

Decades later, the case has returned to the cultural spotlight through Netflix’s true crime series and countless documentaries. Social media platforms, particularly TikTok, have revived debates about whether the brothers were victims or villains, introducing the case to a new generation who were not alive when the trial first unfolded.

The combination of Hollywood dramatisation and internet discourse has reignited public sympathy in some corners, while others accuse the brothers of manipulating narratives of abuse. The renewed attention has also led to a surge in interest in court transcripts, psychologist testimony, and family interviews.

The true crime phenomenon

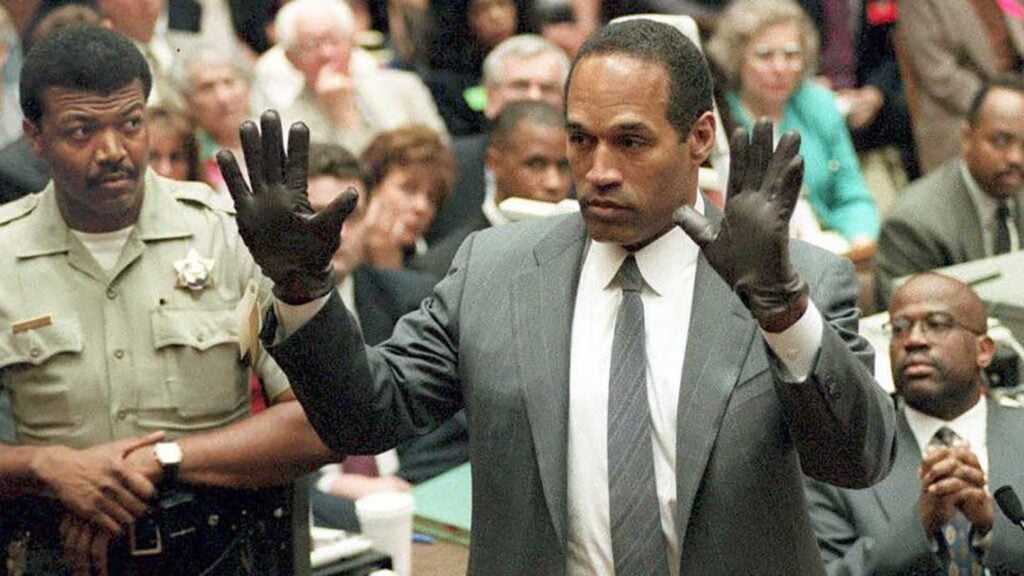

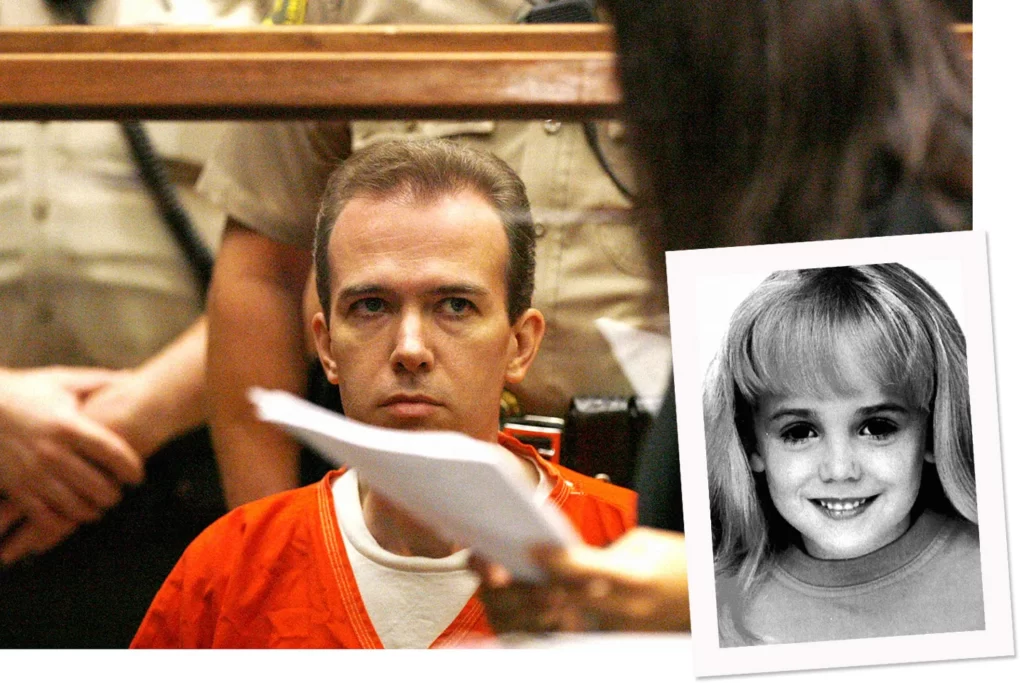

The Menendez case is one of several 1990s crime stories — alongside the O.J. Simpson trial and JonBenét Ramsey case — that have been repackaged for modern audiences. Streaming platforms, hungry for content, have found true crime to be one of their most bankable genres.

Critics argue that this true crime boom often commodifies grief and tragedy, reducing complex human suffering into binge-worthy entertainment. The line between awareness and exploitation is thin: while some productions shed light on systemic failures in justice, others risk sensationalising trauma, retraumatising families, and turning victims and perpetrators alike into characters for mass consumption.

What comes next

For Erik Menendez, the denial of parole means at least three more years behind bars. His brother Lyle’s fate now rests in the hands of a separate parole panel, while the brothers continue to pursue clemency and a possible new trial.

Meanwhile, the Menendez murders remain both a family tragedy and a cultural phenomenon, resurfacing again and again in the public imagination — a reminder of how true crime can linger in collective memory long after the courtroom doors have closed.

Also read: SAG Awards: The winners and nominees list in full

For more videos and updates, check out our YouTube channel

With information from: Nardine Saad and Christal Hayes – BBC