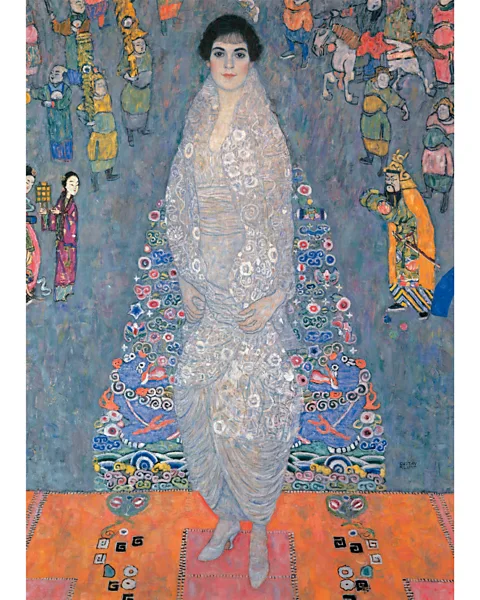

Hidden for decades from public view, the artist’s Portrait of Elisabeth Lederer has now sold at auction for a record sum. Why is it so valuable?

A mysterious and relatively little-known painting by Gustav Klimt is now the most expensive work of modern art ever to sell at auction and the most expensive ever to be sold by Sotheby’s. The teasingly complex canvas, a full-length portrait of Elisabeth Lederer, the daughter of the Austrian artist’s most committed patrons, fetched $236.4m (£180m) in New York on 18 November, far outpacing the price paid two years ago for Klimt’s Lady with a Fan, 1917-18, which broke records when it sold for $108m (£82m) in London in 2023, making it the most expensive painting ever sold at auction in Europe.

The sale saw Klimt’s canvas pass Andy Warhol’s portrait of Marilyn Monroe, Shot Sage Blue Marilyn, 1964 (which sold at Christie’s in New York in 2022 for $195m), to become the second priciest work of art ever to go under the hammer, behind Leonardo da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi (Saviour of the World), c 1500, which sold in 2017 for $450.3m (£343m). But what is it about this nearly 2m-tall likeness of a 20 year-old heiress, whose eerily elongated figure seems to chrysalise in a cocoon-like gown of shimmering white silk, that commands such a jaw-dropping price tag?

On its surface, Bildnis Elisabeth Lederer (Portrait of Elisabeth Lederer), 1914-16, may seem to lack the overt opulence of better-known paintings from Klimt’s so-called “Golden Period”, the era in which he produced such glimmering works as his Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I, 1907, and The Kiss, 1907-8. Where those sumptuous masterpieces glisten with the glamour of the Vienna Secession (the influential movement emphasising artistic freedom that Klimt helped found), the lyrical likeness of Lederer, created in the last years of the artist’s life (Klimt died in 1918, aged 55), pulses with a more psychologically teasing intensity. The canvas’s aesthetic riches are copious, if more concealed.

Seized by Nazi officials, who confiscated the Lederer’s vast collection of Klimts after Austria’s annexation in 1938, the portrait resurfaced into the market in the early 1980s. It was then that it entered the private holdings of the billionaire heir to the Estée Lauder cosmetics fortune, Leonard A Lauder, who died in June 2025. Hidden for decades from public view, the portrait has, in a sense, been biding its time, waiting to return to the spotlight. Whatever the price tag, the mysterious work is poised finally to reveal its secrets. Its extraordinary story blurs fact and symbolism into a richly charged visual tapestry whose intrigue extends into and outside the painting’s surface.

“Culturally complex details”

Undertaken in the opening years of World War One, the portrait’s prismatic exaltation of Lederer – the daughter of August and Serena Lederer, one of Vienna’s wealthiest Jewish families – can be read as the last glorious gasp of the Golden Age from which it emerged. At first glance, the elaborate array of deceptively ornamental East Asian-influenced motifs – that orbit the young woman in a dazzling timeless stage of celestial blue – and the implosive calm of her dark eyes transport us from the accelerating turmoil of European history, transcending time and place. The audacity of gold on which Klimt previously relied has not so much disappeared as been transmuted, in a kind of reverse alchemy, into a fearlessness of vibrant, evocative colour that borders on the boldness of Expressionism.

Look closer and the portrait bristles with teasing and culturally complex details. Within the design of Elisabeth’s elaborate robe and gown, Klimt has woven an enchanting conspiracy of shapes. These echo the contours of symbols and forms drawn eclectically from East Asian art and from the world of microscopic medical imagery that was just coming into sharper focus within the scientific circles in which Klimt moved in Vienna. The dragons on her robe are reminiscent of Qing Dynasty textiles, where such creatures represent cosmic authority and the divinely sanctioned authority of the emperor. Their slow, circling movement around Elisabeth’s thighs, rising from stylised waves, gives her an almost mythic presence as a tamer of the elements and supernatural beasts. By immortalising Elisabeth’s beauty in such mythic terms, Klimt is not simply flattering his patrons. He is, in effect, reinventing Botticelli’s Birth of Venus for a new age.

But there’s more. Offsetting this grand, imported iconography from East Asia are subtler shapes that call to mind the infinitesimal biomorphic forms with which Klimt became preoccupied while attending lectures on cell theory and anatomy delivered by his friend Emil Zuckerkandl, the Chair of Anatomy and Pathology at the University of Vienna, in 1903. A closer look at Elisabeth’s intricate garments reveals a scatter of ovoid and concentric circles that can easily be dismissed as mere floral decoration. These soft, looping amorphous forms and cell-like motifs rhyme richly with similar shapes that appear in several of Klimt’s earlier works, where writers have linked their presence to the artist’s growing interest in embryology, haematology, and the structures of early life.

Read across such works, including Klimt’s earlier paintings Danaë, 1907, and The Kiss, these cellular shapes begin to cohere into an inchoate language that only Klimt could coin. By juxtaposing symbols of imperial power with hints of biological origins and bloodlines, he creates a portrait that works on ever deepening levels of ancient mythology and modern science.

More remarkably still, these subtle references to lineage and identity cast an uncanny light on what happened to Elisabeth years later, under Nazi rule. Decades after Klimt’s death, in the late 1930s, Elisabeth found herself facing increasing restrictions and growing peril because of her Jewish ancestry. In an extraordinary act of self-preservation, she falsely claimed that Klimt, a non-Jewish artist known for his many romantic affairs, was in fact her biological father. Elisabeth’s mother, Serena, corroborated her daughter’s fabricated claim by signing a sworn affidavit. The authorities accepted the fiction and granted Elisabeth a revised status that protected her.

Elisabeth’s story, both inside and outside the frame of Klimt’s mysterious portrait, is one of extraordinary transformation, rebirth and metamorphic survival. Zoom back out from the tight tease of subtle shapes that define the texture of the exquisite garments that Klimt wove for her, and the young woman’s very physique seems surreally to mirror the proportions of a butterfly (a recurring motif in Klimt’s art) just breaking free from its silken chrysalis. Her colourful gown, falling elegantly behind her, suddenly has the look of slick, prismatic wings about to spread dazzlingly wide. Whether Klimt’s late masterpiece is deserving of the astonishing sum it has just fetched, there is little doubting the power and pricelessness of his portrait’s endlessly regenerative genius.

Also read: Beauty Evolution & Letshelp Charity Foundation present: “Be The Light”

Source: Kelly Grovier – BBC